Ballpark Trends of the 2010s: A Decade in Review

By: Cole Shoemaker

12/30/19

Huge structural changes in Major League Baseball are often synonymous with each passing decade in the minds of generations of baseball fans.

The breaking of the color barrier is associated with the 1940s, relocation and expansion captures the 50s and 60s, the height of multipurpose stadiums and Astroturf conjures up images of the 70s and 80s, and an explosion of “retro” ballparks and steroid use define the 90s and 2000s.

Changes in baseball in the 2010s have been much more subtle, but they have everything to do with how the game is played on the field and how fans are supposed to “experience” a game at the ballpark.

Indeed, the changes were actually significant, but they were more evolutionary than revolutionary. There was no expansion, no relocation, no significant structural changes to the scheduling system (other than the extra wildcard), and no game-altering rule changes. Moreover, only 3 new ballparks opened in the 2010s compared to over 20 in the 90s and 2000s.

Instead, due to the increased use of advanced analytics, fans saw a continued slowing of the pace of the game and longer game times.

Much has been written about this, as the time of the game increased to 3 hours and 10 minutes by the end of the decade. This is an all-time high despite explicit efforts to reduce game times. More problematic are the statistics on balls put in play, where fans see one once every 4:17, a full minute less than 10 years ago. Walks, strikeouts, and home runs are up, multi-hit rallies, hit-and-run plays, stolen bases, and old-fashioned offensive tactics are down.

In essence, there is simply much less “action” on the field, at least as one would traditionally define it (you can read more about how this is happening in this SI piece, my source for these numbers).

But I want to discuss how ballpark operations are attempting to respond to this trend on the field, which has huge implications for what team executives envision as the new “ballpark experience” in an epoch of ever decreasing attention-spans.

Major League Baseball experienced a 7% per-game decline in ticket sales during the 2010s, joining only the tumultuous 1960s and the stagnant 1930s as decades where paid attendance decreased. Yes, ballparks are getting smaller, and yes, teams are increasingly relying on other sources of revenue (long-term media deals, TV contracts, marketing partnerships, etc.) but this is still an issue.

In the face of these figures, we hear a lot about Major League Baseball wanting to reverse these trends on the field, but ballpark executives are taking matters into their own hands, accepting the changing nature of baseball as a fait accompli and attempting to turn the ballpark into a revenue generating machine separate from the game and a destination in its own right.

Before the 2010s, ballpark enthusiasts and stadium nerds threw around the term “mallpark” in characterizing the post-1990 baseball-only venues. I think that term was overused.

While the “retro” parks of the 90s and 2000s had mall-like amenities like food courts and kids’ play areas, the primary focal point was still the game on the field, coupled with a genuine (if sometimes poorly-executed) attempt at cultivating attractive aesthetics. Yes, starting in about 2008, we saw many ballparks start to overemphasize the former at the expense of the latter, but there were still architectural sensibilities lingering.

In my opinion, only starting in the 2010s (either in new ballparks or renovation projects), did we start to see ballparks billing flashy, over-the-top amenities as the primary selling point of the “ballpark experience,” in what Rob Neyer memorably dubbed the commercial era of ballparks.

Opening in 2017, Atlanta’s SunTrust Park is baseball’s first true “mallpark,” where almost everything is about amenities and functionality with little attention to architectural principles or original design flares.

The selling point of a Camden Yards (1992) or a Coors Field (1995) was that it had an authentic urban sensibility with contextually appropriate retro architecture (and also had restaurants and luxury suites). The selling point of more recent ballparks is that they have nightclubs for millennials and zip-lines for kids (and are also wrapped in an attractive cloak). Amenities are the centerpiece of ballpark marketing brochures. Architecture and baseball are the afterthought.

I should reiterate that the proliferation of these “fan-friendly” amenities is not necessarily a bad thing when looked at alone, just when they come at the expense of architectural and aesthetic sensibilities.

Luckily, the vast majority of these 2010 ballpark trends occurred through renovation projects to already solid post-1990 baseball-only venues. While only 3 new ballparks saw their first game this decade, 9 opened in the 1990s and a staggering 12 debuted in the 2000s, so we’re mostly talking about welcome enhancements to ballparks that were not originally envisioned as primarily being centers of commerce.

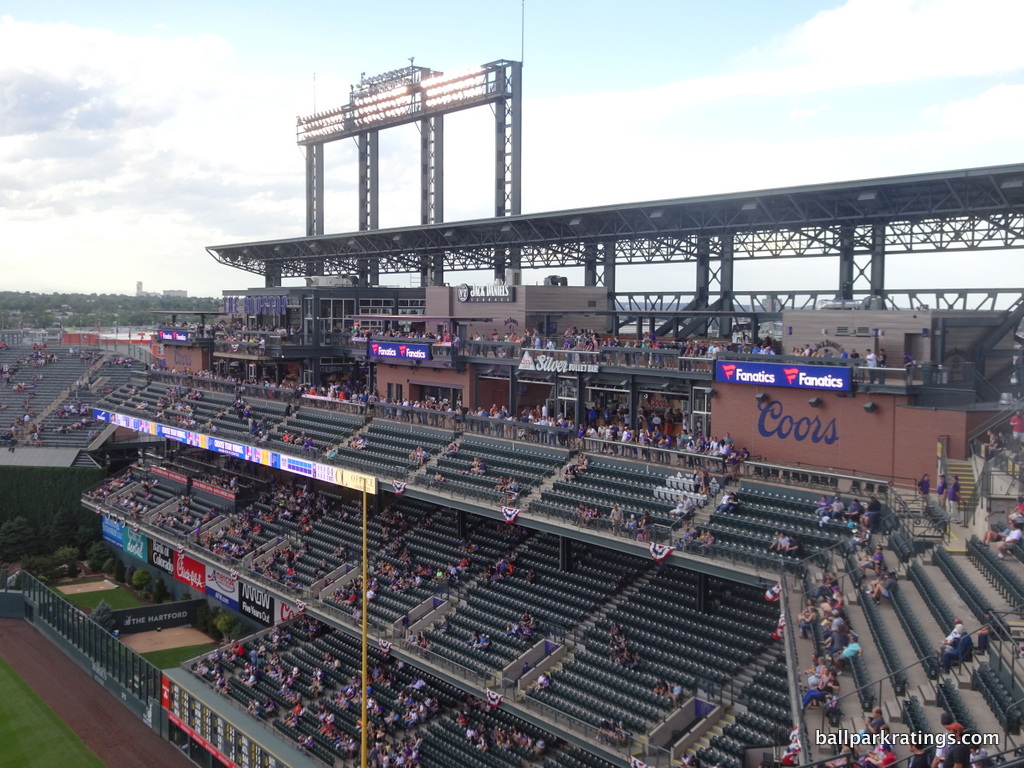

Multi-year enhancements to parks in Cleveland and Colorado show that these changes can be executed in keeping with an overarching aesthetic vision.

From the advent of “social spaces” to the dawn of mixed-use development communities surrounding ballparks, the following enhancements are aimed at generating new streams of revenue by attracting nominal (and non) baseball fans to ballparks as destinations in their own right. I think that is perfectly fine as long as ballparks are still beautiful, and a traditionalist can watch a game free from these diversions if he or she so chooses!

This is seen as a pressing necessity in a game whose pace is increasingly in conflict with society’s more dynamic entertainment options.

“Social Spaces” Galore

While previous modern ballparks invited fans to leave their seats and “explore” the park from different vantage points—think open concourses and outfield standing room only areas—the trend of standalone, destination “social spaces” really accelerated in the 2010s.

The idea is straightforward: no matter the location of their ticketed seats, fans want more expansive spaces to gather with large groups of friends and family to watch the game.

Given the increasingly leisurely pace of the action and longer game times, even diehard fans may want to stretch, hang out, and watch the game from a more comfortable vantage point for an inning or two, all while being able to more easily converse with their companions.

Added by as many as 15 teams this decade, these outfield social spaces vary in size but usually feature free lounge seating, drink rails, varied concessions, and prime standing room areas, all anchored by a large destination bar. Social spaces have often either replaced more formal sit-down restaurants or been placed in formerly dormant areas of the ballpark. In 3 ballparks, these social spaces have displaced large sections of outfield seating (usually in the upper deck) in an effort to decrease standard seating capacity.

Social spaces are also in demand due to the rise in cheap standing room only (SRO) tickets geared toward millennials, which are often sold as a season pass and combined with one alcoholic beverage voucher.

Nationals Park kicked off the decade with its enhanced “Scoreboard Walk,” and it was quickly followed by a batters’ eye rooftop bar at Camden Yards (Baltimore), the bi-level corner bar at Progressive Field (Cleveland) and other rooftop bars at Comerica Park (Detroit). Other standout concepts that were either refashioned or added include Seattle’s “The Pen,” San Francisco’s Kale Garden, San Diego’s Craft Pier, and St. Louis’s multi-tiered Budweiser Terrace.

Renovated spaces in Cincinnati, Kansas City, Toronto, and Minnesota show an increased emphasis on these more flexible areas at the expense of stuffy restaurants, replacing these static, sit-down eateries that began to lose appeal at the ballpark in the 2010s. Even a ballpark as uptight as Yankee Stadium got in on the act.

Two of these new MLB ballpark destinations deserve special attention. Displacing large parts of the upper deck in right and center field, perhaps the model “social space” is Coors Field’s Rooftop in Colorado. Baseball’s best multi-level party deck features two indoor bars, numerous drink rails, upgraded concessions, fire pits, and cabanas. Incredible happy hour deals entice fans to get their early, turning the least desirable part of the ballpark into a must-see for fans.

Perhaps the most notable new “social space” derives its attention from replacing one of baseball’s most polarizing landmarks: Tal’s Hill in Houston. Minute Maid Park’s new four-level center field scene added three new destination bars, a Shake Shack, group tables, and a premium field club. Although, the areas accessible to all fans are regrettably bereft of the lounge spaces, bar stools, and areas to sit down seen at other ballparks.

Ask team executives and folks involved in the industry, and they will tell you that these new gathering areas are the trend that defined ballparks (and ballpark renovations) in the 2010s.

Obviously, these new social spaces are closely related to trends in the food and beverage department that we look at below.

Increased Quality and Variety of Local Food Options

One could write a lengthy piece on the history of ballpark food—from hot dogs and cracker jacks to sushi and poke—but it’s clear that the 2010s brought fans:

(a) an increase in quality of all types of fare due to an influx of local concessionaries and better performance by food service corporations;

(b) more breadth and depth in the variety of cuisine; and

(c) most notably, a dramatic decrease between the “haves” and the “have-nots” both within ballparks and between ballparks.

Ballpark food gradually got better starting in the early 90s at the dawn of the retro era, with Seattle’s T-Mobile Park (1999) and San Francisco’s Oracle Park (2000) traditionally having the best reputation in the stadium food industry. But in terms of sheer variety, there was a significant chasm from ballpark to ballpark. At the beginning of the decade, you could find anything you wanted at ballparks on the West Coast and in New York. In, say, Cincinnati? Not so much.

By 2019, nearly every MLB ballpark is putting its best foot forward, as there is simply not as much differentiation from ballpark-to-ballpark. Yes, some are still obviously better than others, but in terms of the sheer variety of types of food available, you could come away impressed with the breadth (i.e. BBQ, Mexican, Asian, etc.) at the vast majority of venues, a few laggards notwithstanding.

Moreover, with the decline in white tablecloth “Stadium Club” restaurants, the gap in the variety and quality of fare accessible to the average fan and the premium seat holder has decreased. 2010s “premium” increasingly marks its appeal through all-inclusive experiences, not just access, so the fare available on the main concourse (if you’re willing to pay, of course!) isn’t that much worse.

But what most broadly defines the 2010s in ballpark food is the increase in concession stands run by local eateries. Teams are more willing to partner with existing establishments in providing higher-quality fare.

While past ballparks would sprinkle in a regional food item or two for local flare, Citizens Bank Park (2004) was perhaps the first to primarily emphasize local eateries, as landmark Philadelphia restaurants anchor the park’s entire concession presentation.

Ranging from San Diego to Cleveland to Milwaukee, teams overhauling their culinary options in the 2010s have followed this trend.

The quintessentially 2010s ballpark is filled almost exclusively with local, higher-quality fare. San Diego’s Petco Park is the posterchild, as everything—Seafood, Mexican, Asian, Sandwiches, Burgers, BBQ, etc.—is showcased by the region’s best institutions.

Think of something as standard as ballpark burgers, which were reputed for their terrible quality 20 years ago. As kids, we were always told to avoid the burgers and go for the hot dogs if you were going to a baseball game. Today? Think burger joints like A.J. Bombers (Milwaukee), Hodad’s (San Diego), H&F Burger (Atlanta), Chuburger (Colorado) and Shake Shack (Houston, D.C., New York, and Philadelphia).

Yes, we all know stadium locations of many eateries fail to meet the standards or expectations of the original locations, but this is a welcome trend compared to the more prevalent generic Aramark stands of decades past.

Aside: One ballpark trend of the 2010s that I don’t care for is the rise of expensive, super-sized, gimmick foods, which I suggest you avoid and ignore.

2010s Craft Beer Trend Hits Ballparks

Entire books have been written about both the tale of baseball and beer and the craft beer explosion of the 2010s, so it’s only natural that the two have collided rather dramatically. It seems like a lifetime ago when the new Busch Stadium (2006) was derided for its meager selection of Budweiser products.

By 2019, Major League Baseball was so enthralled with the craft beer craze that 9 teams totally eschewed sponsorships with the Budweisers and Millers of the world and actually partnered with local breweries!

It’s a prime example of how ballpark operations coincide with awesome societal trends. The local selections are nothing short of incredible. Even compared to the improving ballpark food landscape, there aren’t many significant laggards here.

Ballparks are filled with new Brewpubs, Beer Halls, and Draft Rooms, fitted with monikers like “Craft Kave” and “Craft & Draft.” More than 10 ballparks have over 50 varieties available. 3 ballparks have their own breweries! (SunTrust Park’s Terrapin Taproom in Atlanta, Citi Field’s Mikkeller Brewery in New York and Coors Field’s Sandlot Brewery in Colorado).

In my opinion, the leaders are San Diego’s Petco Park (including an entire concourse of craft kiosks!), Milwaukee’s Miller Park, Cleveland’s Progressive Field, San Francisco’s Oracle Park, Seattle’s T-Mobile Park, Cincinnati’s Great American Ballpark, Philadelphia’s Citizens Bank Park, and Chicago’s Guaranteed Rate Field, in no particular order. But year after year teams are ratcheting up their craft beer quality and selection.

The latter ballpark in Chicago probably gets the most attention for its Craft Kave at ground level in right field, which rolled out an astounding 91 different beers throughout the 2019 season.

Videoboards and Tech Make a Quantum Leap

In what is likely the most salient transformation of the decade, virtually every park has transitioned to a state-of-the-art, high-definition videoboard system. In the 2000s, small videoboards were anchored by large matrix boards, but those are totally a thing of the past (the only remnant is Arizona’s woeful corner out-of-town scoreboards).

Only Baltimore’s Camden Yards, Pittsburgh’s PNC Park, and Tampa’s Tropicana Field possess main video systems that could be construed as inadequate (and even that’s a stretch), as the proliferation of gigantic shiny screens has been almost uniform.

How remarkable was the 2010s videoboard arms race? Just take the fact that the videoboard at Major League Baseball’s second newest venue, Marlins Park (2012), now places 20/30 in size! Most ballparks that installed new systems did so in the mid-2010s.

Given space available in left field, the video system added at Cleveland’s Progressive Field in 2016 (measuring 221-feet wide and 59-feet tall) probably won’t be outdone any time soon, however.

We’re getting to the point of diminishing marginal returns in size, as all of these videoboards are more than adequate in displaying information and broadcasting replays. Whatever obsolete means shouldn’t indicate inadequacy.

Going into the new decade, Cincinnati’s Great American Ballpark just installed baseball’s first all LED display system in high-dynamic-range format (HDR). So, the beat goes on.

Is Ohio baseball looking to prove its tech prowess, or what?

Premium Seating Continues to Evolve: Fewer Luxury Suites, More All-Inclusive Clubs, More Flexibility

In the 1990s, individual corporate luxury boxes were all the rage in the game of premium seating, with some ballparks building over 120 of them, a tough sell even in the 90s given an 81-game slate. It was one-size-fits-all for the well-to-do fans who generated (and still do) the vast majority of the money for a ballpark.

Suites were complemented by modestly priced “club level” seating on the mezzanine, but these club levels weren’t all that upscale by today’s standards, as the main selling point was access to a climate-controlled concourse with marginally better concessions and bars. Membership “Stadium Club” restaurants rounded out the premium services as the only truly upscale space available other than luxury suites.

All of this got turned on its head in the 2000s across sports, particularly baseball, as the corporate appetite for traditional luxury suites subsided for a variety of reasons and teams realized the untapped potential of ultra-premium all-inclusive club seats.

Well-heeled fans wanted flexibility and value, and for the right price, individual tickets behind home plate (sometimes labeled “Diamond Clubs”) often included amenities like access to an upscale lounge, theatre style seating, all-inclusive food and alcohol, and fun perks like lockers and batting cage views.

The majority of ballparks that debuted in the 2000s featured these very exclusive home plate clubs, minimized the quantity of their luxury suites, and shrunk the size and increased the quality of their mezzanine “club levels.”

The 2010s in sports put the ultra-premium all-inclusive club experience on steroids, where virtually every good, lower-level seat is an exorbitantly priced premium seat. Of course, given that only 3 MLB ballparks opened in the 2010s, we only see this at full fruition at Atlanta’s SunTrust Park (2017): multiple all-inclusive field clubs, dugout lounges, a minimized mezzanine club, flexible options like premium terrace tables, and only 32 full-season luxury suites.

MLB teams in the 2010s have undertaken some interesting renovations in this department (hybrid club-suite experiences, loge boxes, etc.) centered around flexibility, but it’s nothing that would make all good lower-level seats a high-priced premium club seat.

But we will see something like that at Arlington’s new Globe Life Field in 2020, which is more aligned with where sports have been in the latter half of this decade.

While the new ballpark’s relatively high number of luxury boxes is a genuine outlier in baseball, all seats in the lower bowl in between the foul poles are premium/semi-premium, and thus restricted to ticketholders. Even Yankee Stadium and SunTrust Park don’t go that far. Pre-game autographs or selfies with players for those in the nosebleeds? Forget about it. Comparatively affordable mezzanine club levels for fans who just want a touch of premium? Forget about it.

Those paying a pretty penny to sit in the lower bowl get exclusive access to “The District” concourse, which also features an all-inclusive speakeasy and first base club. Others get access to an all-inclusive home plate club or dugout lounges at field level.

Going forward, we will see continued “ballpark gentrification” by making each and every seat close to the field a premium or semi-premium seat. But, fortunately for most fans at least, most MLB ballparks are a bit behind what you’ll see in the NBA or the NFL (read: more fan-friendly) at the high end.

The Beginning of Ballparks Anchoring Mixed-Use Development

While the most successful ballparks of all-time—from Wrigley Field of the jewel box era to Camden Yards of the retro era—derived much of their lore through their authentic contextual integration with existing urban communities, the new model is to couple stadiums with contrived entertainment centers.

Indeed, the history of baseball is closely related to America’s voyage from rural to urban to suburban back to urban and now to faux-urban. All sorts of entities are realizing the potential of mixed-use development, and teams are looking to tap into new revenue streams by controlling activity outside the park.

Common even in the late 20th century, stadium projects surrounded by parking lots are now a nonstarter. Although, the golden age of ballpark dining and entertainment districts (either within existing suburban or urban communities) will define the 2020s. We only began to see the emergence of this concept in the 2010s, at least in Major League Baseball.

While conceived of decades prior, Busch Stadium’s Ballpark Village in St. Louis was one of the first such mixed-use development projects in the MLB. Opening in 2014, phase one included bars, restaurants, event venues, rooftop seats, and a Cardinals Hall of Fame and Museum. Phase two, expected to be completed by mid-2020, will include apartments and a Loews hotel.

In 2017, SunTrust Park’s Battery Atlanta proved that these mixed-use development projects could serve as a model for financing an entire ballpark. Called a “game-changer” and a “watershed” moment for baseball, the Battery is baseball city, filled with dozens of bars and restaurants, numerous shopping options, a Comcast office building, an Omni hotel, and a Live Nation concert hall.

Other teams are rapidly securing land outside their parks to develop similar projects, as we will see a flurry of such “ballpark villages” with carefully manufactured team “Live! destinations,” “PRB” bars, and “Sports and Social” scenes. This certainly seems more artificial and formulaic compared to an authentic urban environment.

Texas Live! at the Rangers’ Globe Life Field (2020) is integral to the new ballpark’s existence, and similar entertainment districts in Arizona, Oakland, Tampa, Portland, and Montreal will be essential if new MLB ballparks ever open in those locations down the road.

The mixed-use development craze won’t be limited to potential new ballparks. The Colorado Rockies will open McGregor Square next to Coors Field in 2021, San Francisco’s Mission Rock will debut by 2023, a renovated (or new) Angel Stadium in Anaheim will be anchored by a project beyond even the Battery Atlanta, and clubs in San Diego, New York (Mets), and Pittsburgh have bought adjacent lots for similar development.

These new dining and entertainment districts are the most explicit attempt at attracting nominal (and non) baseball fans to ballparks as standalone destinations.